‘I want to question patriarchy’ AJ Public Liberties speaks to Elif Shafak

![Elif Shafak [Ferhat Elik]](https://liberties.aljazeera.com/resources/uploads/2021/05/1621045681.jpeg)

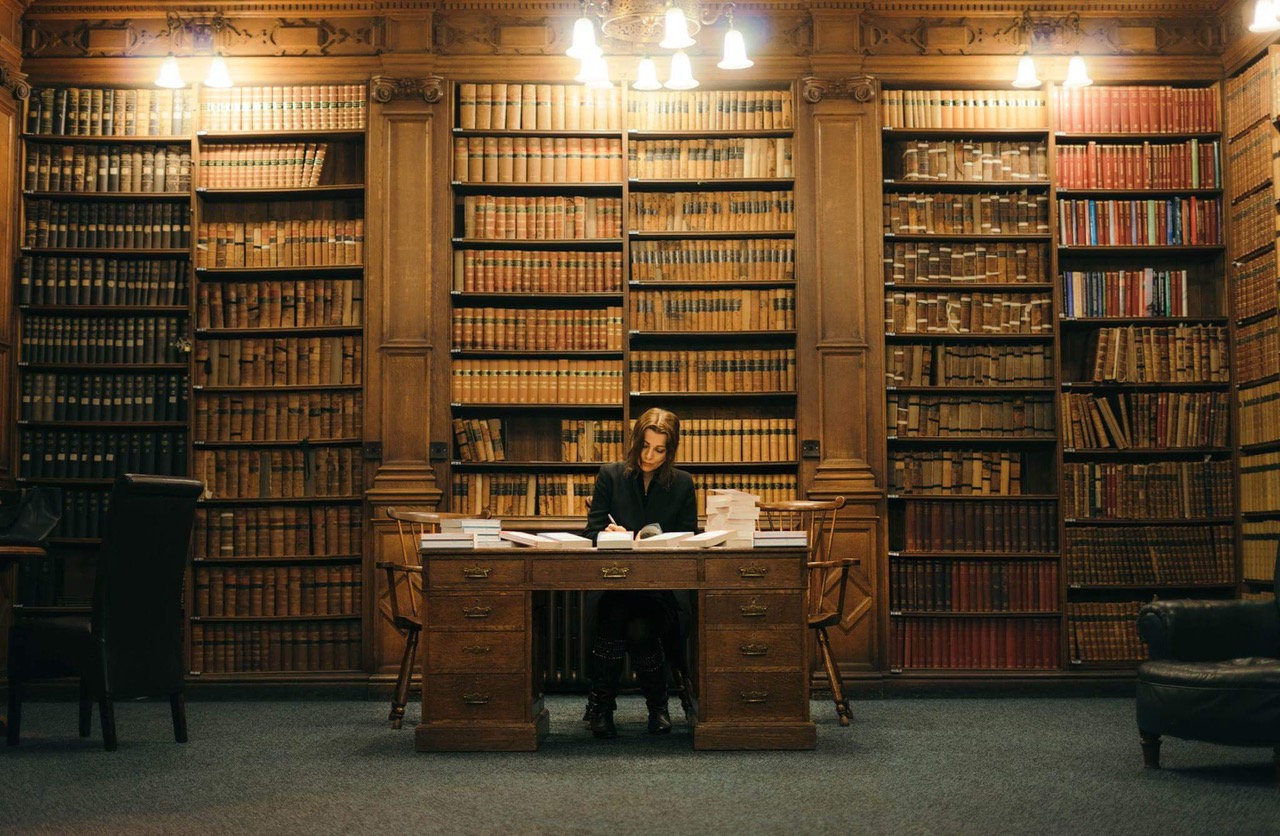

Elif Shafak [Ferhat Elik]

Elif Shafak, the most widely-read female Turkish author, whose new book ‘This Island of Missing Trees’ appears later this year, speaks to Al Jazeera on sisterhood, populism and women’s rights in the Arab World:

Al Jazeera: During the pandemic many people worldwide are longing for home. What do you make of this universal longing for home

Shafak: This idea really resonates with me. It is possible to have more than one homeland. On so many levels I feel emotionally connected to Turkey: to the people, the culture, the food, the music, daily life. I miss it. On the other hand, if I look at the politicians I feel demoralized. The idea of a ‘motherland’ comes with an entire package and we should be able to talk about the good and the bad.

Populists say that if you criticize your motherland it means you don’t love your country. But this is not the case at all. You criticize precisely because you love it, because you care, because you want a better future for your country.

Al Jazeera: Isn’t the idea of a ‘motherland’ also being exploited by nationalistic politicians? Are the current strongmen exploiting people’s yearning for home?

Shafak: It’s very paradoxical and saddening to see how we are witnessing a rise in nationalism, tribalism and also isolationism at a time when we need international solidarity the most. This is a moment when we have massive global challenges ahead: whether it is the possibility of another pandemic, cyber-terrorism, climate emergency. As we are speaking our planet, our only home, is burning. All of this shows that we are interconnected, deeply interconnected whether we like it or not.

So it is just an illusion to think that by erecting walls you are isolating or insulating yourself from other people’s problems. I think it is wiser, healthier, to understand the importance of international solidarity and international sisterhood but what we are witnessing right now is the exact opposite: focus on nationalism. And yes it is usually propagated by so-called “strong men”. This emphasis on a certain form of jingoistic masculinity goes hand in hand with populist nationalism.

We live in an age in which emotions guide and misguide politics. And politics guide and misguide emotions. I think we need to talk about emotions – a topic that is usually underestimated in political science. Emotions like anxiety, fear, anger, bitterness, uncertainty – all of these emotions are very important if you want to understand the state of politics today.

Unfortunately, populist demagogues seem to understand the power of emotions far better than their democratic counterparts. This is another paradox of our time. We need to think more carefully about why people are anxious or fearful or angry. Populism is a phony answer to some very real problems. It is a lie and an illusion that populism will solve our social and political problems – it will make things worse.

Al Jazeera: To what extent are you trying to break down stereotypes and trying to tell a more global story?

Shafak: I do question dualities a lot -both the dualities and the cliches that come along with them. I do question the cliches that come with it, the cliche of West versus East for example. Ever since my childhood I have had my share of this East-West commute a lot. I have always questioned the sweeping generalisations that come attached to the West or the East. I want to examine, and ultimately debunk the myth of patriarchy which is a universal phenomenon that exists everywhere across the world. But it is worse in some parts of the world. We in the Middle East need to face this fact.

I always focus on untold stories- people who have been pushed to the peripheries. I want to give more voices to the voiceless, empower the disempowered. I also know there are so many people who are open minded, who are global souls.

Unhappiness increases when democracy declines, when inclusion declines, when equality declines. If people are not given a sense of equality of course they are going to feel more and more trapped. It is not a coincidence that when unhappiness increases mental health problems also tend to increase. I don’t think we talk about mental health enough.

AJ: What is the role of nostalgia in people’s attraction to populist politics?

Shafak: Nostalgia is such a core issue in populist rhetoric because it is connected to this idea that once upon a time there was a golden era that we should all aspire to go back to. That, too, is an illusion. That golden era never was. It all depends on who tells the story of history. Unfortunately, populist politicians all over the world, in America, India, Hungary, Turkey etc, play into this idea. Sometimes it manifests itself in an imperial nostalgia: even the time before nation state is used as a dream of Empire to aspire to.

But if you ask the story of the Ottoman Empire to a Kurdish peasant, or an Arab farmer, a Jewish or Armenian or Greek artisan or a miller in the Balkans, or if you ask a concubine in the imperial harem what life was like for her, for instance….. it would be a completely different story than the one we read in history textbooks at school. If women were to tell the story of the Ottoman Empire it would not be the same story at all. If minorities had a chance to share their lived experiences, that, too, would be a completely different account. But their voices have been mostly unheard, their stories are untold, sometimes erased. Turkey is a country with a rich history but collective amnesia.

Al Jazeera: How does one counter this false representation or manipulation of the past?

Shafak: We need books, knowledge, nuanced way of thinking, empathy, we need literature. The memory of the art of storytelling is much stronger than the amnesia created by day-to-day politics. If you live in a place where books are not freely written, it becomes even easier for one official narrative to assert itself from above. In the end all nation states have their own official interpretation of the past. In that regard I don’t see much difference between states.

But there is a crucial difference between countries with a relatively better democracy and countries where there is no democracy: in a democracy you can walk into a bookstore and easily buy books that challenge that official narrative, you can easily read investigative journalism and you can find other voices and plural stories. In a place where there is no democracy all the other his-stories or her-stories will be suppressed, censored, systematically erased.

AJ: You say you ‘tell stories’ but some stories you tell are also political. Can you step in and out of it and say ‘it was just a story’?

As a storyteller, of course, I love stories, I believe in stories, but I am equally drawn to silences.I have always been sincerely very interested in this dance between sorrow and humour and I believe in life there is both, especially if you come from a wounded democracy, from a country where there is complex history, you will see lots of melancholy and sadness and ruins but at the same time these elements of humour.

I respect humour a lot and I think for our mental health and our collective health we should never lose sight of humour. By humour I don’t mean the kind of sarcasm that looks down on other people. I love compassionate humour, egalitarian humour. I also make fun of myself. We are all part of the same cycle.

But the topics I deal with are quite heavy and sometimes it affects my own psychology. There are days when I cry when I write. It is not as if I am immune to the emotions in my stories. Literature does not have to be autobiographical necessarily, but I believe there has to be an emotional connection between the story and the storyteller.

Al Jazeera: What is your view of Turkey’s recent withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention? How important is the Convention?

Shafak: I think the Istanbul Convention is the most progressive regional convention we have had to protect women and children from violence. It is incredibly important. It has been signed by 45 countries plus the EU. Turkey was the first country to sign it. And now instead of implementing the Convention Turkey is withdrawing from it. The Convention opens shelters for women who have nowhere to go to; it provides legal assistance to victims and it also provides psychological assistance. It ensures that perpetrators of violence are jailed or kept away. It gives legal and police protection to women. So there are all these layers that are sorely needed, so the fact that the Turkish government has withdrawn from the Convention is hugely problematic but on top of this, it is doing so at a time when there is a rise in femicides, a rise in gender violence so it is doubly problematic.

AJ: Femicides have not been officially reported on in Turkey after 2009. Who is keeping the tally?

Shafak: Yes, the authorities in Turkey stopped sharing data since 2009. So there are no official numbers, and this silence is very problematic. But there are women’s rights organisations, such as We Will Stop Femicide Platform, that are heroically trying to keep a tally. This is not easy because there are murders that go unreported, then there are also suspicious deaths that are called “suicides” but if you really dig into the story you see that it wasn’t suicide. So the actual number of cases of violence against women is much higher.