The Rohingya’s Perilous Seas & Possible Exits

Archive/ Reuters

Off Malaysia’s northern coast, another tragedy has unfolded.

A wooden boat carrying roughly 300 Rohingya refugees went down near Langkawi over the weekend, leaving hundreds missing and at least seven confirmed dead. Malaysian authorities, who have been combing the waters along the Thai border, managed to pull thirteen survivors from the sea.

Officials say the group had set out from Buthidaung in Myanmar’s Rakhine state only three days earlier. To avoid detection, the passengers were reportedly split between smaller vessels as they approached the coast. Two of those boats have yet to be found. Images released by Malaysia’s maritime agency show survivors burned, skeletal, and stunned being helped aboard rescue craft, too weak to stand.

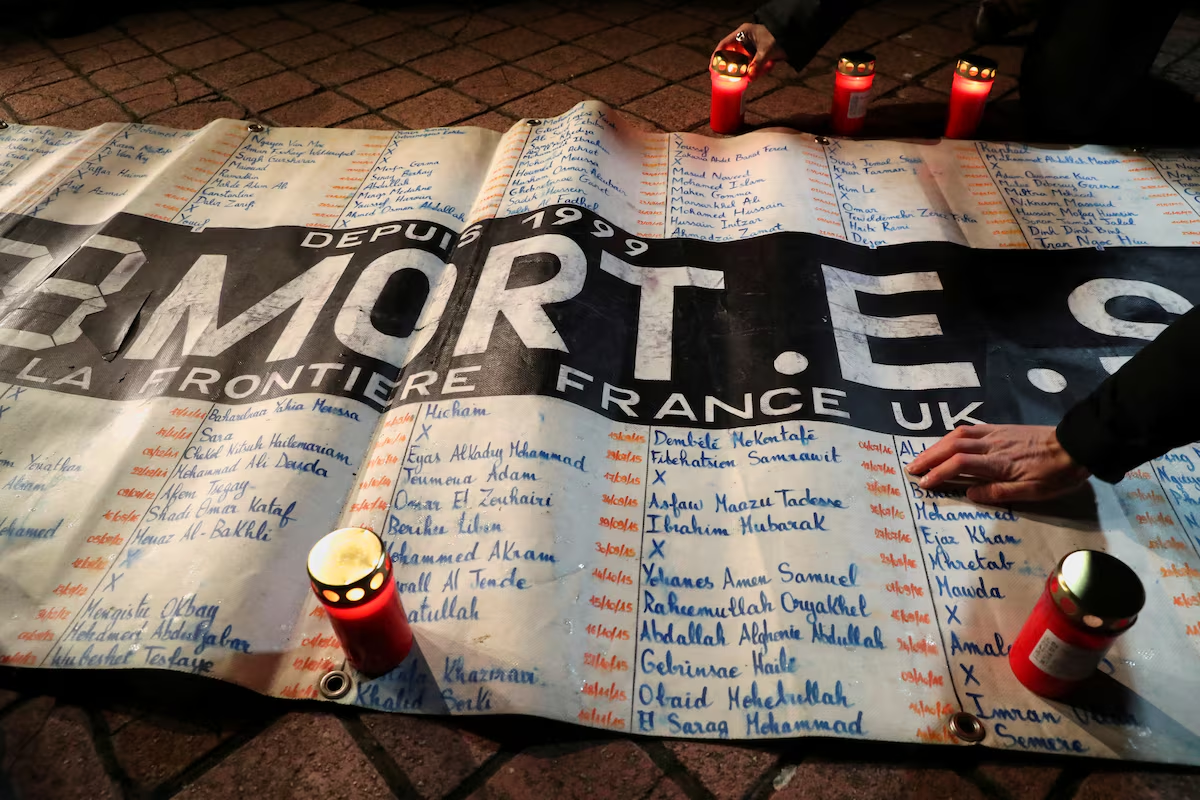

For the Rohingya, scenes like this are no longer exceptional.

Once a quiet, farming community in western Myanmar, they have become the region’s most persecuted and stateless people. Decades of discrimination were followed by a brutal military campaign in 2017 that forced around three-quarters of a million into neighbouring Bangladesh.

There, in the sprawling camps of Cox’s Bazar, more than a million people now live in limbo, trapped between a homeland that rejects them and host countries that tolerate them only begrudgingly.

The sea, though perilous, offers one of the few possible exits. Each year, between October and April, when the waters of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea are calm, thousands attempt the voyage towards Malaysia or Indonesia. They travel on decrepit, overcrowded boats operated by traffickers who demand impossible fees and often abandon them mid-journey.

The UN estimates that over 5,000 Rohingya have risked the crossing this year alone; about 600 are dead or missing.

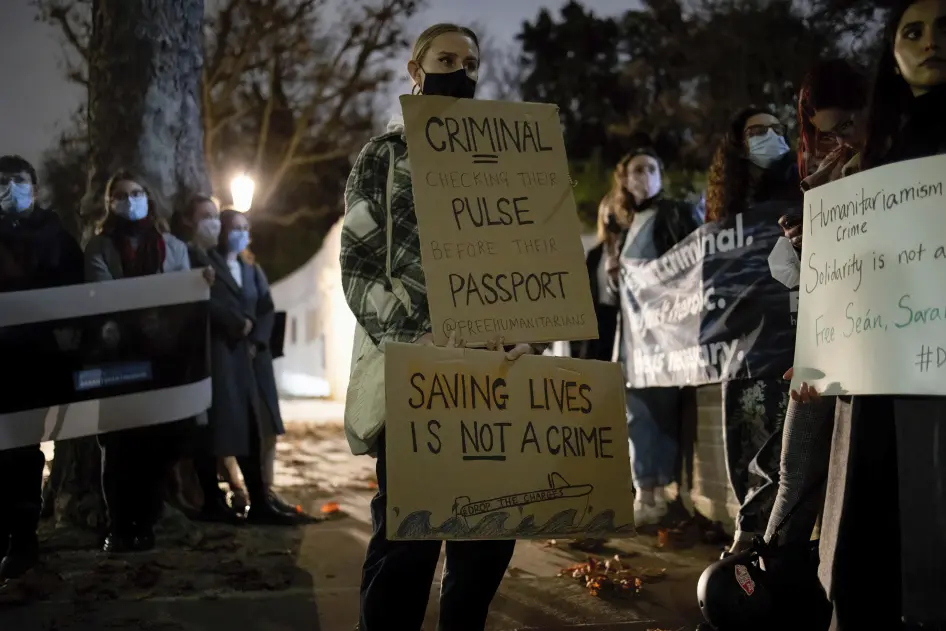

Every sinking exposes more than the cruelty of smugglers; it lays bare the paralysis of regional politics. Governments in Southeast Asia continue to treat the crisis as someone else’s problem, offering little more than ad hoc rescue operations and short-term detention. Despite years of UN appeals for shared responsibility, a coordinated system of search, rescue, and safe migration remains elusive.

As monsoon winds fade and calmer seas return, more boats will inevitably set out from Myanmar’s western shores. Without serious regional cooperation, the Andaman and the Straits of Malacca will keep claiming lives, silent memorials to a people stripped of a country and a future.