‘The Revolution does not happen overnight’: Philippe Sands on ecocide and its links to Nuremberg

Philippe Sands

Philippe Sands QC is an author, barrister and professor of law at University College London.

He co-chairs the Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide with Senagalese lawyer Dior Fall Sow. The panel revealed a draft definition of ecocide in June.

Sands has acted as counsel in more than two dozen cases at the International Court of Justice, many involving environmental law. In 2019 he represented the Gambia in its case against Myanmar involving Myanmar’s alleged violation of the 1948 Genocide Convention.

He is the author of 14 academic books as well as East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity published in 2017. His latest book is The Ratline: Love, Lies and Justice on the Trail of a Nazi Fugitive.

He spoke to Al Jazeera about his work on ecocide, the origins of his interest in environmental law and his hopes for the movement to criminalise the destruction of the environment.

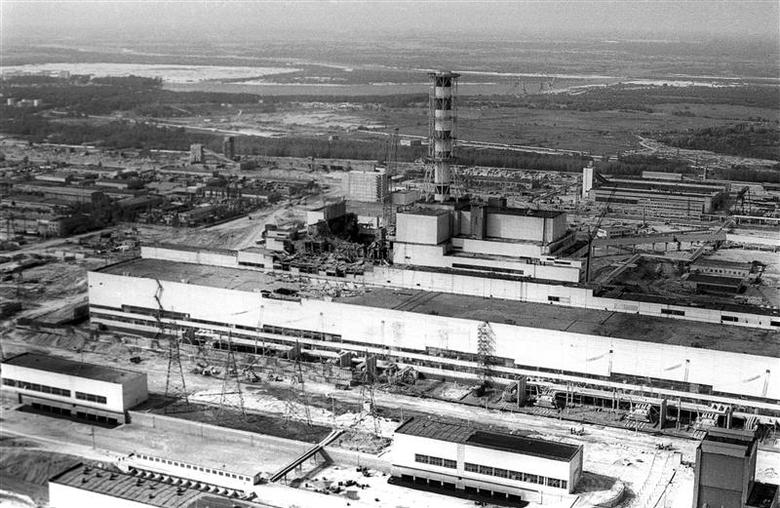

Al Jazeera: You have stated that your environmental awakening occurred with the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. How did this happen?

Sands: On 26 April 1986 I was in Cambridge, England. It began with rumours. We started getting news reports, tiny bits at the bottom of the paper. And it grew and grew. And it soon became apparent that it was a very major accident and that there was a major cover up. It then became very relevant in the UK because the cloud came over Europe and it reached Britain and they had to close sheep farms and some of these farms are still closed to this day because the fields cannot be used for grazing.

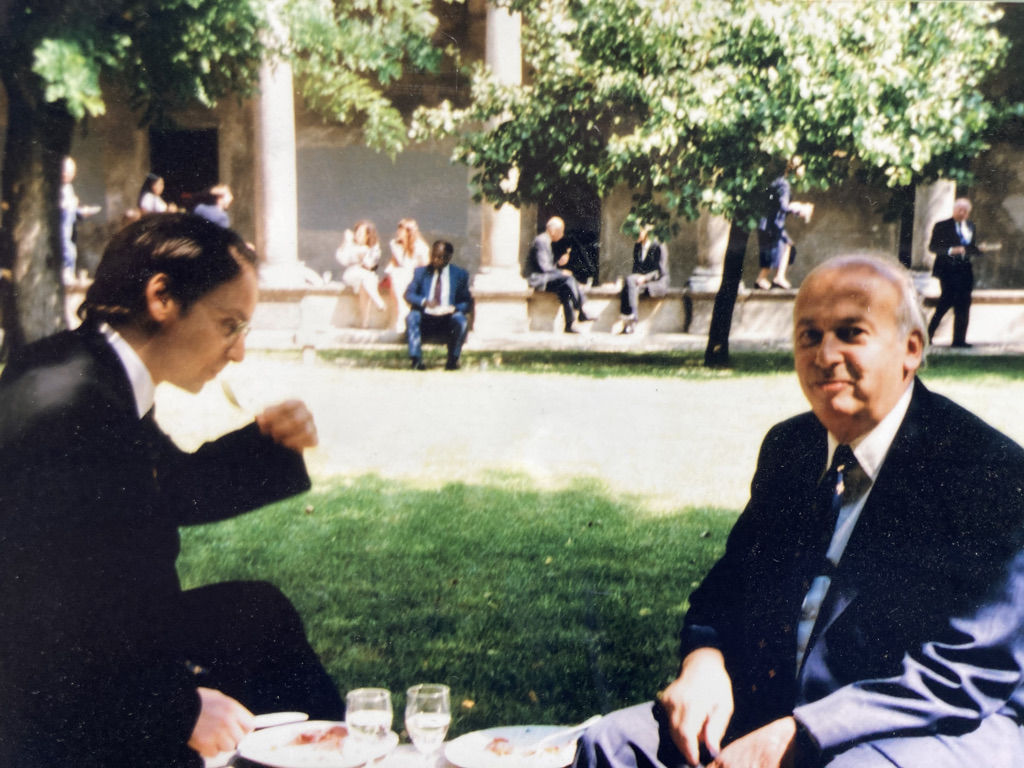

At the time of the Chernobyl disaster I was 25 years old. I was in Cambridge working with Eli Lauterpacht on investor state arbitration. Chernobyl happened and out of the blue I got an invitation to research the international legal aspects of Chernobyl namely what were the obligations of the Soviet Union to the rest of the world substantively and in terms of providing information to neighbouring states. So I started looking into it and it was completely fascinating because it was pre-international environmental law. The subject literally didn’t exist. I thought this is interesting so I wrote a paper and I then published a book with all the relevant legal documents.

The book then caused me to be contacted by Greenpeace to join their delegation at the International Atomic Agency. It was the first time I travelled to Vienna and I visited to my grandfather’s house -an interesting coming together of events. I then spent two years working with Hans Blix and Mohamed El Baradei.

I then started doing more and more work for Greenpeace. I got hired to write an opinion on Japanese scientific whaling. I then co-founded a Centre for International Environmental Law which still exists today in Washington DC but I am no longer involved. From 1990 I negotiated the UN Convention on Climate change for all the small island states. Then in 1994 I published my textbook on international environmental law. It all came out of Chernobyl. If Chernobyl hadn’t happened none of this would have happened.

Philippe Sands with Elihu Lauterpacht [Courtesy of Philippe Sands].

Al Jazeera: Will the crime of ecocide have a deterrent effect on those who are destroying the environment?

Sands: The really interesting and surprising thing is that the media requests to attend the launch of the panel’s work on ecocide did not come only from the usual suspects. It has come from publications such as Fortune Magazine, The Economist, The Financial Mail and the Wall Street Journal. So its crossed a threshold. It is not seen as a boutique little thing. I was slightly surprised by this but also encouraged. So someone out there in that world is listening.

What I’ve said is that criminalising ecocide might contribute to a changing of consciousness. This is my hope for it. And maybe there is an overlap between that and deterrent effect. What we are saying is that the protection of the environment is something that we take so seriously that we are now going to harness the power of the criminal law to achieve its greater protection and wellbeing. We know in the context of domestic law, in the fields of financial services, money laundering and elsewhere that the risk of personal criminal corporate liability absolutely has a deterrent effect. Criminal law does concentrate the mind. But criminalising ecocide on the international level, as an international crime, will only work if it has a trickle down effect into domestic law, as is the case with genocide and crimes against humanity. If a state becomes a party to the ICC it has to change its domestic law. This is where our hope lies. If it doesn’t happen at the level of national law it will not happen.

Al Jazeera: In your book East West Street you wrote on the contributions of Rafael Lemkin and Hersch Lauterpacht to defining genocide and crimes against humanity respectively. Does ecocide have a similar champion? Could ecocide not have been listed as a crime against humanity instead of it being an independent international crime?

Sands: The decision to include crime against humanity in the Nuremberg Charter happened very privately. It happened at a meeting between Robert Jackson, the prosecutor at Nuremberg, and Hersch Lauterpacht.

Jackson trusted Lauterpacht. So Jackson goes to Lauterpacht’s house and all Lauterpacht does is to say ‘you need titles and I think you should use ‘crimes against humanity.’ And Jackson thought ‘what a great idea’. But it wasn’t sold as Lauterpacht’s idea. Lauterpacht got no credit for it. The Americans introduced the headers into the text and sold it off as their own. Only in his report to the US President, after the trial was over, did Jackson make a passing reference to an academic who helped him. He didn’t mention Lauterpacht. Lauterpacht’s role was extremely important because it meant that Jackson would know he has a serious intellect behind him.

Crime against humanity are committed against people. The essence of that crime is the protection of people. Ecocide is committed against the environment. We wanted to make the protection of the environment an end in itself. For that reason ecocide cannot be another crime against humanity.

Ultimately we’ve taken the clothing of genocide and the innards of crimes against humanity. You cannot have a standard of intentional destruction of the environment because no one intentionally seeks to do that. Ecocide is always going to be the result of recklessness, negligence or wanton behavior instead. You can therefore not take the genocide model contained in the 1948 Genocide Convention.

Interestingly if you call it an ‘environmental crime against humanity’ no one cares but if you call it ‘ecocide’ people sit up and say ‘oh yes that is very important’. We have done some polling about this in the context of the expert panel. We are taking Lemkin’s magical word and giving it the machinery articulated by Lauterpacht.

Al Jazeera: The panel’s definition balances environmental harm against social and economic harm. This definition of ecocide has already been criticized by legal academics such as Kevin Jon Heller as being anthropocentric. How do you respond to this?

Sands: The idea of ‘social and economic harm’ was taken from another part of the ICC Statute where there is a weighing up of military advantage against social and economic advantage. We cannot say, particularly to developing countries that they cannot take those benefits into account. States will not sign up to a definition of ecocide which is not going to allow them to pursue legitimate societal objectives. It’s a way of moderating. It’s a consensus document drafted by twelve people with very different backgrounds, some very pragmatist, some very idealist. This reflects what we will encounter in the attitudes of states. There are going to be compromises. We had to find a way to limit it to the most egregious forms of damage. My objective at this stage at this stage was simply to come up with a text that governments could agree with.

Al Jazeera: The panel’s focus is the International Criminal Court. How about creating an international environment court?

Sands: States do not want such a court. And ultimately I am not in favour of creating such a court. When environmental issues have come up at the International Court of Justice the issues have not been purely environmental issues. Think of the Pulp Mills case and the Australian whaling case. The environment is not self contained so there is no real way that a court that dealt only with the narrow environmental issues could ever address broader systemic societal issues which raise environmental issues. Ultimately I am not in favour of a specialist environmental court because in my experience issues don’t get decided in that way. Approaching the ICC is the fastest way of getting the most states to sign up.

Al Jazeera: On the 75th anniversary of the Nuremberg trials in November 2020 you stated ‘The revolution does not happen over night. This is a long game. That’s where we are with international criminal justice. Its two steps forward, one step sideways, one step back.’ Are states ready to criminalise ecocide?

Sands: Its been 75 years since the Nuremberg trials and the formulation of the international crimes which are now contained in the Rome Statute. One explanation for why there are currently only four ‘core’ international crimes is the innate conservatism of international lawmakers. The crucial question is whether the Zeitgeist is ready for change. And my sense is that it just might be. States are responding with interest. The Red Cross is responding with interest. Young people are completely fascinated by the crime of ecocide. I’ve been surprised by the positivity of the reaction. And there seems to a convergence of issues between climate change and the Covid crisis. People have this sense that things that they cannot control and this has created a new solidarity.

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.