The International Criminal Court: A Historical Background and Growing Challenges

From the outset, the ICC faced significant obstacles.

The International Criminal Court (ICC), established in 2002, stands as the world’s first permanent court tasked with prosecuting individuals for the gravest crimes of international concern: war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and the crime of aggression. Its creation marked a historic shift in international law, reflecting the global community’s commitment to addressing atrocities that transcend national borders. The establishment of the ICC was, however, not an overnight decision but the result of more than half a century of evolving legal principles and a broader understanding of justice in a post-war world.

The origins of international criminal justice can be traced back to the aftermath of World War II, which left behind a legacy of unprecedented atrocities and a pressing need for accountability. The Nuremberg Trials, held between 1945 and 1949, represented the first international attempt to prosecute major war criminals, specifically Nazi leaders, for their roles in the Holocaust and other crimes committed during the war. Although groundbreaking, the Nuremberg Trials were limited in scope and temporary in nature, focused only on specific individuals from one war, and reliant on the victorious Allied powers for enforcement.

During the Cold War, international efforts to establish a permanent international court faltered. But with the end of the Cold War, and the genocides in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the international community recognized the need for a more structured and permanent mechanism to ensure accountability for grave violations of international law. In response, the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 1993 and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in 1994. These ad hoc tribunals sought to bring justice to the victims of ethnic cleansing, genocide, and other war crimes in these regions, but they were seen as temporary solutions to a larger, systemic problem.

Amid these developments, the international community began working toward a permanent court capable of handling crimes of this magnitude on a global scale. The culmination of these efforts was the Rome Statute, adopted in 1998 by 120 countries, which created the ICC. The statute came into force in 2002, when the ICC began its official operations in The Hague, Netherlands. The court’s jurisdiction was established to handle cases where national courts were unwilling or unable to prosecute crimes such as genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

At its core, the ICC was designed to be an independent, impartial institution that would serve as the world’s final judicial recourse in cases of the most heinous crimes. Its jurisdiction is complementary to that of national courts, meaning it can only act when states are either unwilling or unable to prosecute. The Rome Statute’s provisions sought to ensure that perpetrators of atrocities would face justice, regardless of their status, position, or nationality.

However, from the outset, the ICC faced significant obstacles. One of the most glaring challenges was the non-ratification of the Rome Statute by powerful nations, including the United States, Russia, and China. While the ICC’s founding members embraced the court’s mission, these three permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) were notably absent from the list. Their reluctance to join the court reflected concerns over sovereignty, potential legal consequences for their citizens, and, in some cases, fear that the court might target their own leaders in the future.

Despite these challenges, the court has pursued justice with determination. Over its first two decades, the ICC has indicted numerous individuals, including high-profile cases such as the prosecution of Thomas Lubanga, a militia leader convicted of recruiting child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the ongoing prosecution of Omar al-Bashir, the former president of Sudan, for his role in the genocide in Darfur. Additionally, in 2023, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin for war crimes related to the illegal deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children, a charge Russia vehemently denies.

While the ICC has made significant strides in prosecuting crimes and bringing attention to serious global issues, its efforts have been hindered by multiple challenges. The most notable among these is the reluctance of states to cooperate with the court, particularly in enforcing arrest warrants and handing over suspects. Countries such as Russia, China, and the United States have refused to cooperate with the ICC in specific cases, thereby limiting the court’s ability to operate effectively. This lack of cooperation has often led to frustration within the ICC, as the court has had to rely on the goodwill of member states to apprehend and surrender suspects.

In recent years, the ICC has faced mounting pressure from powerful countries, particularly Russia and the United States, over its investigations into their leaders and military actions. These tensions have reached a boiling point, with both nations taking direct actions to undermine the court’s work.

Russia’s Retaliation

The ICC’s most significant investigation in recent years has been its probe into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2023, the court issued an arrest warrant for President Vladimir Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, accusing them of being responsible for the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia during the ongoing conflict. This move was unprecedented, as it was the first time the ICC had issued an arrest warrant for a sitting head of state.

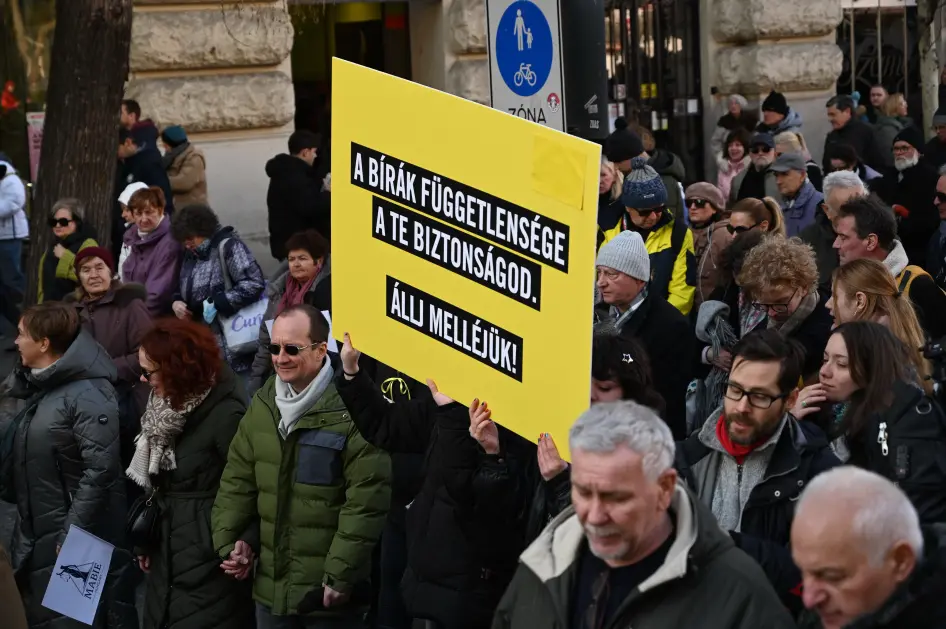

In retaliation, Russia issued arrest warrants for ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan and several judges involved in the investigation. This was seen as an aggressive attempt to intimidate the court and deter its efforts to hold Russia accountable for its actions in Ukraine. Judge Tomoko Akane, the president of the ICC, condemned these actions in a forceful speech at the court’s annual meeting in December 2024. She emphasized that these individuals were facing arrest warrants “merely for carrying out their judicial mandate in accordance with the court’s statutory framework and international law.” Russia’s actions, she argued, were an assault on the court’s independence and the very principles of international justice.

In addition to Russia’s actions, the ICC has also faced significant pressure from the United States, which has long been an opponent of the court. Although the U.S. is not a member of the ICC, it exerts considerable influence on the global stage, particularly through its political, economic, and military power. The U.S. government has consistently opposed the ICC, citing concerns over its jurisdiction, particularly its potential to prosecute American nationals.

This opposition reached a peak in 2020 when the Trump administration imposed economic sanctions on ICC officials after the court opened an investigation into potential U.S. war crimes in Afghanistan. The Biden administration has not reversed these sanctions, and in fact, further tensions arose in 2024 when the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill proposing additional sanctions in response to the ICC’s investigation of Israeli officials, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, for alleged war crimes in Palestine. Although the U.S. has made some conciliatory statements, its position on the ICC remains largely antagonistic.

As the ICC faces increasing political and legal challenges, questions about its ability to remain effective persist. Legal experts like Sergey Vasiliev have warned that the court’s legitimacy could be jeopardized by selective enforcement of its mandates, with powerful states undermining its authority and avoiding accountability when it is politically inconvenient. The Washington Post editorial board recently raised concerns about the ICC’s credibility, particularly in light of its arrest warrants for Israeli officials, suggesting that the court had failed to address crimes in non-member states like Syria, Myanmar, and Sudan. However, these critiques often fail to acknowledge the legal limitations the ICC faces, as countries like Syria and Myanmar have not ratified the Rome Statute, and the UN Security Council has not referred these cases to the court.

Despite these challenges, the ICC continues its work, pushing forward with investigations into some of the world’s most pressing conflicts. In addition to ongoing investigations in Ukraine, the court has also targeted leaders like Min Aung Hlaing of Myanmar for crimes against humanity. The growing tension between global powers and the court underscores the broader challenge facing international law: the fight for accountability in a world dominated by geopolitical interests.

As we enter the third decade of the ICC’s existence, the institution stands at a crossroads. It faces formidable opposition from some of the world’s most powerful nations, including those who sit on the U.N. Security Council. Yet, the court’s unwavering commitment to its mandate—to prosecute individuals for the most heinous crimes—remains. The growing challenges to its authority, while troubling, are a testament to the court’s continued relevance in the global pursuit of justice. How these challenges unfold in the coming years will shape not only the future of the ICC but also the very principles of international justice that it upholds.

The ICC’s ability to adapt to these challenges, ensure cooperation from states, and maintain its legitimacy will be crucial in determining whether it can continue to serve as a beacon of hope for victims and a deterrent to those who would commit atrocities. As the institution navigates this complex political landscape, the stakes are high: the future of global justice, accountability, and the rule of law are inextricably tied to its survival and effectiveness.

References:

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998) – The founding treaty of the ICC. You can find the full text on the official ICC website.

- International Criminal Court Official Website – Provides extensive details on the history, mission, cases, and ongoing activities of the ICC. https://www.icc-cpi.int/

- “The Nuremberg Trials: A Brief History” – The Nuremberg Trials website or scholarly sources such as books on the Nuremberg Trials.

- United Nations – For the role and history of the UN Security Council and its relationship with the ICC. https://www.un.org/

- “War Crimes and Justice” by Richard Ashby Wilson – This book provides an in-depth look at how international law responds to war crimes and the establishment of the ICC.

- Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International Reports – For information on cases involving countries like Israel, Syria, and Myanmar that are relevant to ongoing ICC investigations.

- The Washington Post and other major media outlets – For recent editorials and discussions surrounding the ICC’s role in international law, its investigations into Israel and Russia, and the political challenges it faces.

- Sergey Vasiliev’s works on international law – His writings, particularly on the effectiveness of the ICC and legal implications of non-cooperation by state parties, could provide useful references on the subject.

- U.S. Congress Bills and Executive Actions – These documents would provide insights into the U.S. government’s stance on the ICC, including sanctions and criticisms, particularly in relation to Israel and Afghanistan.

- Reuters.

- AP.