Ali Fowle: ‘I’m somewhere safe’: Journalists hiding from Myanmar’s military

![Pro-democracy protesters and a journalist run as riot police officers advance on them during a rally against the military coup in Yangon, Myanmar, on February 27, 2021 [Reuters]](https://liberties.aljazeera.com/resources/uploads/2021/06/1623931346.jpg)

Pro-democracy protesters and a journalist run as riot police officers advance on them during a rally against the military coup in Yangon, Myanmar, on February 27, 2021 [Reuters]

Three months ago, I was forced to leave Myanmar, the place I had called home for almost a decade. After a military coup on February 1, a lethal crackdown on protests and widespread arrests had made it impossible to safely continue working as a journalist there.

I drove to the airport in the early morning. The streets were quiet, but signs of the chaos that had taken place hours earlier were everywhere. Brick dust stained the streets red. Wire, concrete blocks, and large orange rubbish bins were scattered across the roads – leftovers from the makeshift barricades protesters used in a hopeless attempt to protect themselves from the onslaught of security forces and their bullets. The walls and overpasses were littered with graffiti- three-finger salutes and profanities condemned the coup and the military leaders.

It was an emotional journey. I was leaving friends and loved ones behind to face a situation that only seemed to be getting worse, as I flew back to the comfort and safety of the United Kingdom.

I was right to be concerned. In the weeks following my departure, more and more friends and contacts were arrested. Myanmar’s State TV channel began announcing a daily list of people subject to arrest warrants. As the numbers increased, more familiar names started to appear. Celebrities, activists and politicians, people I had met and interviewed, but also journalists – friends and colleagues.

Most faced charges under the newly amended section 505A of the Penal Code, which broadly targets anyone who encourages civil disobedience..

“I’m just annoyed they didn’t use a cool photo of me,” a friend quipped in a message when I got in touch after seeing his name added to the list. Like others, he had made the decision to go into hiding early, well before the warrant was announced – so at least I knew he was safe. “I look so bad in that photo!” he complained jokingly.

Like many of my friends, he consistently responds with lighthearted humour to his otherwise grave situation. His upbeat attitude makes it easy to forget all he has had to leave behind. His family, his dogs, his friends, his job. He was a well-known TV presenter and he is now hiding in the jungle, washing his clothes in the river and contending with biting insects. “You know me Ali, I love an adventure,” he reassured me. “At least I can walk around safely and go swimming. As long as I don’t think about what happens next or how long I will have to stay, I’m happy.”

Others have not taken the upheaval quite as well. One friend cried as she relayed all she had left behind, describing how she and her colleagues had to sleep in the jungle and drink from rivers on their journey. There are now checkpoints all across the country, and for high profile TV reporters with famous names and faces, crossing them is not an option. They are forced into taking off-road routes through forests and conflict zones to reach safety.

I still speak to people in Myanmar almost every day – checking in with friends and contacting people as part of my news coverage. After a decade of working in Myanmar, journalists and activists make up the majority of my closest friends there. Most have made the decision to flee their homes and go into hiding. For security, we use encrypted messaging apps to speak, but people have also started to regularly change their numbers, and accounts will suddenly go dormant. Sometimes those I have been in regular contact with go silent for a few days or even weeks. It can be difficult not to fear the worst. When I do get hold of them, I have learned from a few awkward exchanges to stop asking people where they are. “I can’t say where I am but I can say I’m somewhere safe,” one friend reassured me recently, the unmistakable sound of cicadas in the background a clue they were no longer in the city.

For those who did not find somewhere safe in time, most I know are being held in Insein Prison, denied contact with friends, family, or colleagues. The mother of one detainee tells me that every day brings more uncertainty. She is apprehensive about making strong statements against the military over the phone but tells me she feels helpless. “If I could turn back time, I would rather be still in January. Because this is not what anybody wants.”

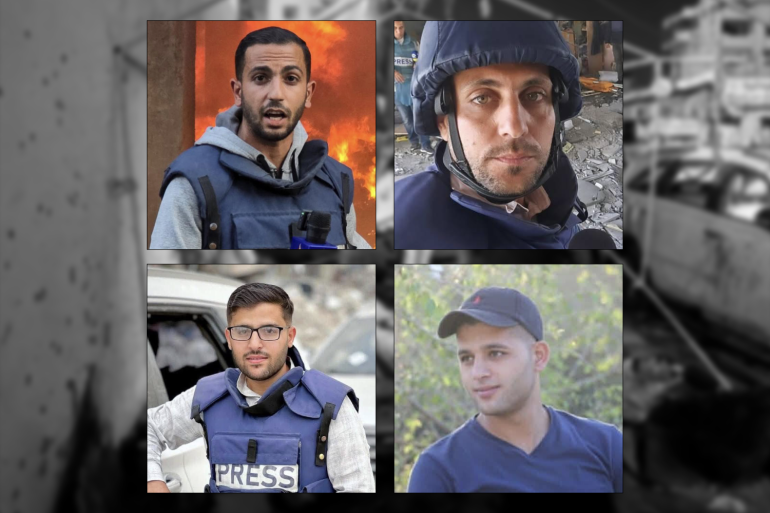

More than 6,000 people have been detained since the coup, and journalists are one of many groups being targeted. Both local and foreign journalists have been arrested. Some have been dragged from their homes in the middle of the night, others apprehended at the airport or while reporting on court proceedings, or taken during raids on their offices. One journalist friend I know was arrested from her home along with her son, a teenager I still think of as a young boy.

Myanmar is dropping out of the news headlines as the world’s interest wanes, but for so many of my friends, their lives have been permanently altered.

After 14 days of no response in early May, one friend I had been particularly worried about suddenly popped up on my phone.

“Hi.” It was from Facebook messenger, a platform most people have been avoiding due to the lack of security. I was wary of whether it was really him but soon a video call came through. He tells me he has been on the run for two weeks and had lost communication with most people. He had reached somewhere safe, albeit temporary, he says.

I have so many questions but I know it is too dangerous to ask. It is best that as few people as possible know where he is. But he is obviously eager to share the story of his ordeal – he tells me he has had to abandon all his belongings. He only has two shirts and a small backpack with him. But he is pragmatic.

“We have to adapt,” he says. “It’s better than torture sessions.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

- Most Viewed

- Most Popular