The Road to Guantanamo: AJ Public Liberties speaks to Moazzam Begg (part 1)

![Moazzam Begg [Reuters]](https://liberties.aljazeera.com/resources/uploads/2021/09/1631545831.jpg)

Moazzam Begg [Reuters]

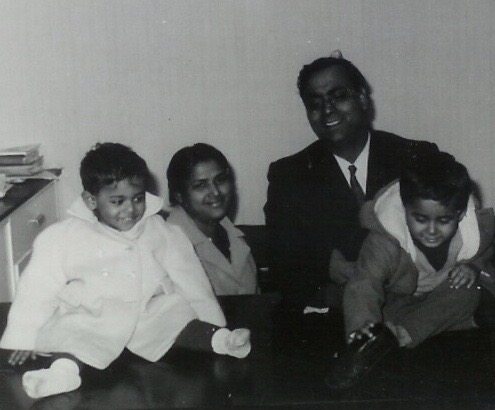

Moazzam Begg, who was born in Britain, was held in Kandahar, in Bagram prison and in Guantanamo prison for a total of almost three years. He was never charged.

During this time he was subjected to interrogation, torture and death threats.

He was released on 25 January 2005. Begg is currently the outreach director of the prisoner rights organisation CAGE.

He spoke to Mia Swart of Al Jazeera Public Liberties and Human Rights shortly before the 20th anniversary of 9/11.

Swart: Where did you grow up?

Begg: I was born and raised in Birmingham in the UK. My parents were originally from Pakistan. I grew up and studied in Britain. I was taught Urdu by my parents. My mother died when I was six years old. And I later studied Arabic. So by the time I was in my mid 20’s I was fluent.

In the mid-90’s I started to rediscover my identity, particularly my Muslim identity and as part of that I took various journeys abroad for example to Bosnia. In 2001 I went to Afghanistan with my family. And then on the 31 of January 2002 there was a knock on my door and I was detained in Pakistan and that was the beginning of my journey in US custody.

Swart: Why did you move to Afghanistan?

Begg: I had been to Afghanistan on occasion prior to this. I have always been fascinated by Afghanistan. Fascinated by its history, by its politics, its ruggedness and the fierceness of the people. The defeat of the Soviets was appealing to me. I heard that the Taliban was in charge and was getting rid of the warlords. And I heard that children who were taken by slaves by these warlords were rescued by the Taliban. So it was not an organisation I did not know much about but it sounded good. At the same time I was hearing that they were backward with regard to education in particular.

I had friends, some Afghans who had connections here in the UK, and they said they wanted to help with education in Afghanistan. They wanted me to to open a girls’ school in Kabul. We helped set up a curriculum. So I went to Afghanistan with my family in 2001. I was helping to run a school. It didn’t make sense to me that people say the Taliban does not allow female education at all. That was not my experience. Perhaps they put restrictions on them. I also went there for a project to build wells in the drought stricken area in the north. Shortly after this the ‘war on terror’ began, the US raids began.

What was driving me was that I had lots of advantages living in Britain and I wanted to use those advantages. in addition to my language skills and impart some of that to others.

Moazzam Begg (left) with his mother who passed away in 1975, his father and his brother. [Courtesy of Moazzam Begg]

In Afghanistan the only resistance to the Taliban existed in the same region then as where they are based now – in Panjshir valley. So there was some fighting there. But everywhere else in the country was safe. I could live there with my family and go to the markets, go to the shops. I took the school children to visit Kabul zoo. We went to trade exhibitions and watched the famous ancient game, Royal Buzkashi, where Afghan horseman display their talent . There were lots happening. But of course Al Qaeda existed there as well. They weren’t present necessarily in Kabul but we knew they existed as an organisation.

I heard the name Osama bin Laden, everybody knew that name. But Osama bin Laden was in Kandahar which was about a 24 hour drive to get to. In Kabul, in addition to people from all over Afghanistan, there were people from different parts of the world. Arabs. Uyghurs and Pakistanis. It was a relatively cosmopolitan city compared to the rest of Afghanistan. But of course when the 9/11 attacks happened all the fingers started to point to bin Laden and he was in Kandahar. Of course bin Laden had friends and supporters in different parts of the country, including Kabul.

But nobody really thought that Kabul was going to get hit the way it did. The first strikes were in Kandahar. I remember that there were strikes on Afghanistan following the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000 but they only struck training camps, not cities. So perhaps naively I thought they were going to do this again, they’re not going to strike cities. The first strikes were in Kandahar but they hit Kabul soon after.

Swart: So you were hanging on. You didn’t plan to leave immediately?

Begg: By then I had been there for 6 to 7 months. So to me it was a place to live in. I was there with my family. We were able to lead a normal life. I had a car and a roof over my head, all those things normal people would have. My children were going to school. I had been a bookshop owner in the UK so I was very connected to education, very connected to books and reading. My income was from the bookshop we had and also I rented out my house in the UK.

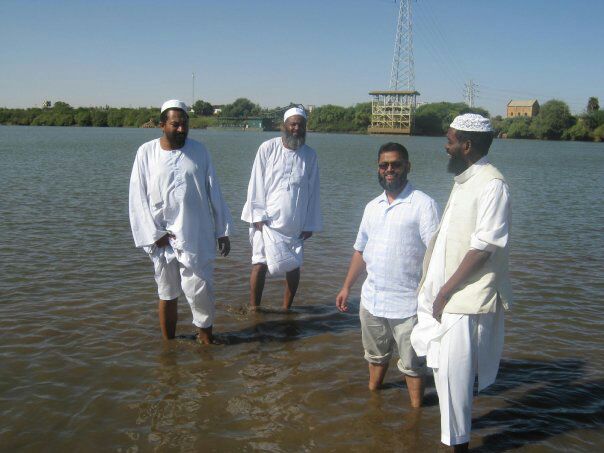

Begg on the banks of the Nile in Khartoum with former Guantanamo prisoners from Sudan. [Courtesy of Moazzam Begg]

Begg: So before I even went to Afghanistan the MI5, British intelligence, came to my house in 1998, knocked on my door at about 6 in the morning. There were 2 agents, 1 police officer. They came and sat down and started talking. They said ‘We are very interested in your friend.’ My friend’s name was Farid Hilali. He had written to me from the UAE to say that he was detained and had been tortured very badly. He asked: ‘Can you please help to get me a lawyer? I have nobody to help me. And they have forced me to sign a confession saying I’m a member of a terrorist group.’ He was being forced to sign a confession by Emirati authorities that he is a member of an extremist group.

I learnt later that there were British agents present when he was being tortured. Now these British intelligence agents came to my house and started to ask me about him and asked ‘how do you know him’ and so forth. And I did not know him so well. He knew me well enough to know I had links to law. I studied law. So this same interrogator who came to my house in 1998, I saw him again in Kandahar as a prisoner of the US when guns were being held to my head.

Swart: So you were on MI5’s radar long before 9/11 because of your bookshop?

Begg: We had a bookshop. We had books about many subjects and also subjects on jihad. Those books contained details of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. This was at a time when the British and Americans supported those fighting against the occupation.

They arrested me about 6 months after 9/11. I had left for Pakistan with my family some time before that. The US bombing began, we saw the cruise missiles and we saw the aerial bombardment.

Before that the Americans dropped leaflets offering $5000 bounty – both in Afghanistan and Pakistan. I had left for Pakistan with my family some time before that. That’s the region they were targeting. That’s when I was detained.

The US had sought bin Laden’s extradition even though no such treaty existed with the Taiban and failed to produce evidence of his involvement in the attack, which the Taliban had asked for.

What sealed my fate was the leaflets offering bounty money as well as very specific intelligence from the British. My friend in Britain who was running the bookshop for me said that MI5 came and asked for me. I said to me friend ‘tell them where I am, give them my number.’ A week later I did talk to them but from behind the barrel of a gun, after they took me to secret detention.

Swart: Why was there not more of a culture of trying to counter this, of trying to fight this?

Begg: What you have is the most powerful nation in the world. These are the largest bombs in modern history – we are talking about bombs that weigh 15 000 pounds.

The US argued ‘even if he is innocent it is better we get rid of them.

I was interrogated by the Americans and the Americans invited the British and and the British started to ask me questions in a way that would not have been allowed to in Britain.

Swart: Why was it necessary for US to bring in UK?

Begg: The US said very clearly: you are either with us or your are terrorists. When they say ‘us ‘ they also meantt Britain , Australia, they mean Canada. They mean the English-speaking world. All of these countries had key involvements in the interrogation process, in the rendition programme, in the outsourcing of torture. They were one and the same. People had to understand they’re together. As such the British had full access to the prisoners. They also had access to all of the prisons.

Swart: Did they torture you in Pakistani custody?

Begg: No not in Pakistan. Pakistan is a prime example of ‘them’. You’re either with us or against us. The majority of prisoners were apprehended in Pakistan.

The president of Pakistan at the time, Pervez Musharraf, writes in his book ‘In the Line of Fire’, that he received a bounty of millions of dollars from the CIA. And this is different from the money promised in those leaflets. One of the things he says proudly to the US, is: you keep saying that Pakistan cannot be trusted but we’ve lost 50 000 soldiers as a result of your war. And we handed over hundreds of people without any legal process. We did away with our law. What he is saying is we did everything and you still don’t trust us.

From Pakistan I was handed to US military custody by the Pakistanis and they took me from there to Kandahar and Kandahar – this new detention site set up by the Americans. That is where the brutality began. In Bagram and Kandahar.

Swart: So the torture started in the prison in Kandahar?

Begg: Yes. It started right there. The humiliation: they ripped my clothes off, they spat on me, there were dogs coming close to my face and snarling at me. They shaved my hair and shaved my beard. And they took photographs. And this was standard procedure. It happened to everyone. I was in Kandahar for about 6 weeks.

Begg’s book ‘Enemy Combatant: A British Muslim’s Journey to Guantanamo and Back’ (Arabic edition) published in 2006.

Swart: From Kandahar you were moved to Bagram…

Begg: Bagram was a holding facility for everyone the US was at war with worldwide. I encountered prisoners sent there from Azerbaijan, Egypt, from the Gambia and many other places. This was the global war on terror.

Bagram is a huge old machinery warehouse built by the Soviet Union. So you can still see writing in Russian on the walls. The ground floor was converted into 6 prison cells. There were at least 20 prisoners in each of these cells.

The cells were made of coils of razor wire. They bring you there with force and tie your hands and leave you suspended from the top of one of the door. And they put a hood over your head and leave you there for hours, sometimes days. They give you a break only to go to the toilet or to eat something.

One the first floor there was a separate area where they conducted the interrogations and they held specific prisoners such as high ranking Taliban prisoners. Inside some of those rooms they had tiny cells – about one and a half meter by one and a half meter. A person can’t even lie down in there. You can only stand. They sometimes kept people there for 4 to 5 weeks. I saw one of the prisoners beaten by the soldiers, they then took him into the room, hung his hands over his head and that’s where he died.

On the first floor they also played really crazy loud heavy metal music. They tie a person’s hands to their legs. They did this to me. They shackled my hands behind my back and shackled my hands to my legs. They also brought pictures of my wife and children. And they pushed the picture in front of my eyes. There was a woman screaming next door. They were torturing her. They asked me: where do you think your wife is? Where do you think your children are? So this is one of the techniques they used .To me Bagram was worse than Guantanamo. They could do anything they wanted to do without any accountability.

And the shocking part of this is that the FBI was fully involved, the law enforcement, the police. The world’s most famous law enforcement agency was taking part.

Swart: In light of the fact that the Americans knew that many of the suspects were innocent, why have there been no apologies and such little acknowledgement. And is there a debate on whether reparations should be paid?

Begg: A US Senate Committee released report on torture in 2014 in which they admitted that they tortured at least 119 prisoners, many in Guantanamo. My belief is it was thousands. But this was their own report. They’ve said that nobody will be prosecuted, in spite of this report. So what this immunity does is allow the torturers to get away with it, it allowed Donald Trump to come in and say that he believes torture works.

Swart: In South Africa we had a controversial amnesty arrangement as part of our truth and reconciliation process but the US had no such process.

Begg: That’s a really important distinction. I’ve been to South Africa and met with some ANC leaders myself. Its an important example, the TRC. You give truth in order to give reconciliation. Here there is no attempt at reconciliation and nobody wants reconciliation. So there can’t be any truth.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.